The Four Core Types of Strategy for Tech Companies

Product Strategy Series - Part 2

In my previous post in this Product Strategy series, I discussed what strategy means in the context of a company (and what it doesn’t mean). I plan to go deep into Product Strategy in this series, but before I do, I want to set high-level context by explaining the four key types of strategy that are relevant to tech companies.

The Four Core Strategies

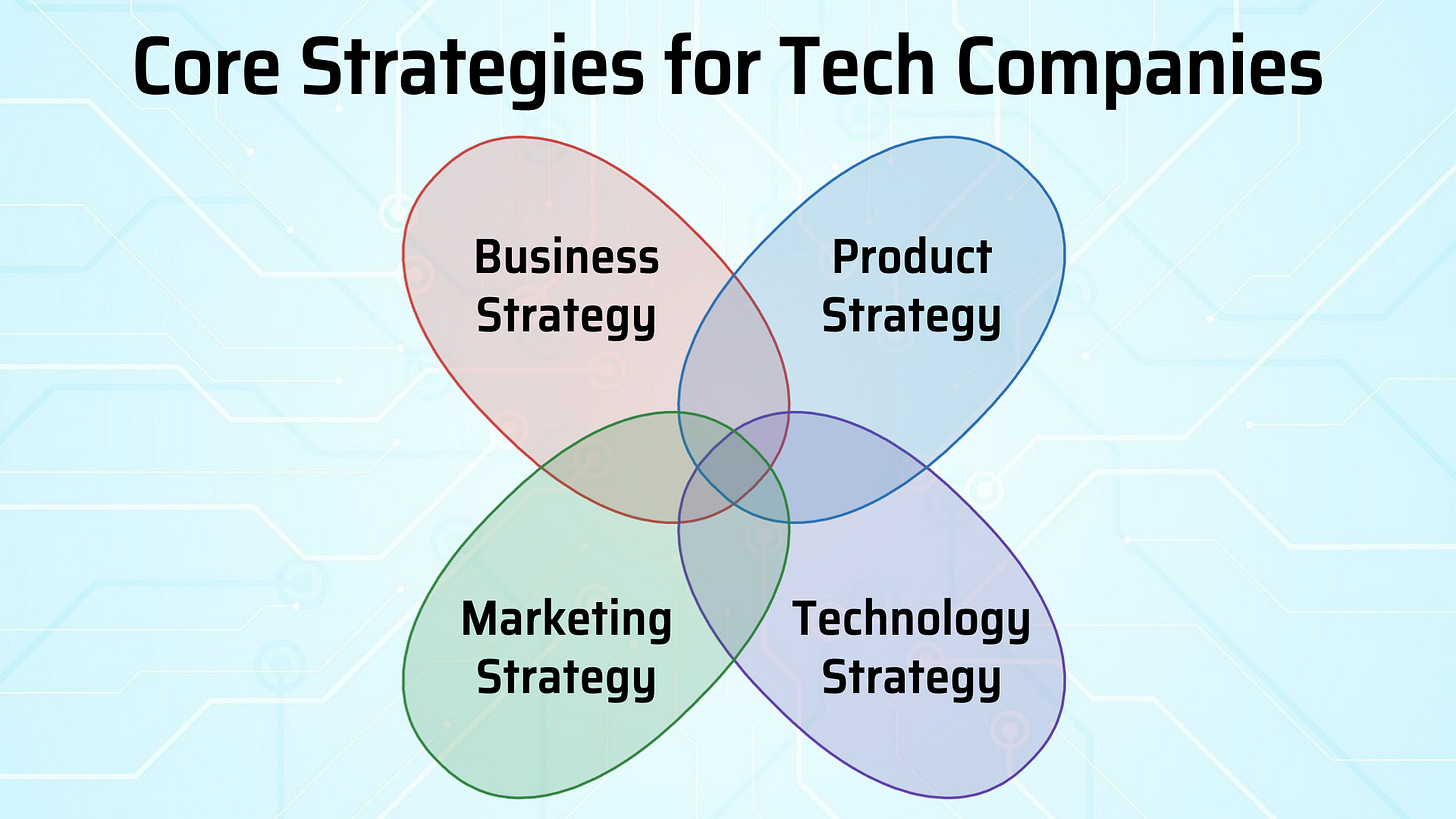

People in companies often use the term “strategy” with various descriptors in front of it: hiring strategy, social media strategy, etc. But most of these are tactics or functional plans, not true strategy. This usage has diluted the meaning of strategy. Based on my experience, there are four categories of strategy that stand out as the principal types of strategy for technology companies:

Business strategy

Marketing strategy

Technology strategy

Product strategy

I’ll describe each of these core types of strategy and illustrate them with examples. Before I do, I want to clarify that my intent in describing these four areas is not that a company should strive to come up with a dominant strategy for each of the four areas. It’s rare enough for a company to have a dominant strategy in just one of the four areas.

In this series, I will make the case that while a company can use any of these four types of strategy to create differentiation, Product Strategy most often offers the greatest opportunity to create more customer value. Your Product Strategy should be informed by your Business Strategy. The four strategy types often have areas of overlap, and your strategies should be aligned. Given the importance of Business Strategy, I will focus on that topic in this post.

Business Strategy

When people use the less precise term “company strategy,” they’re usually referring to business strategy. As an MBA, I studied business strategy in my courses. Most of the popular strategy books focus on business strategy, not product strategy.

From my previous post, my definition of strategy is “a long-term plan based on consequential decisions designed to deliver higher customer value than other alternatives.” If we apply this to business strategy, it means: “What consequential long-term business decisions are we making to deliver superior customer value?”

Porter’s Five Forces

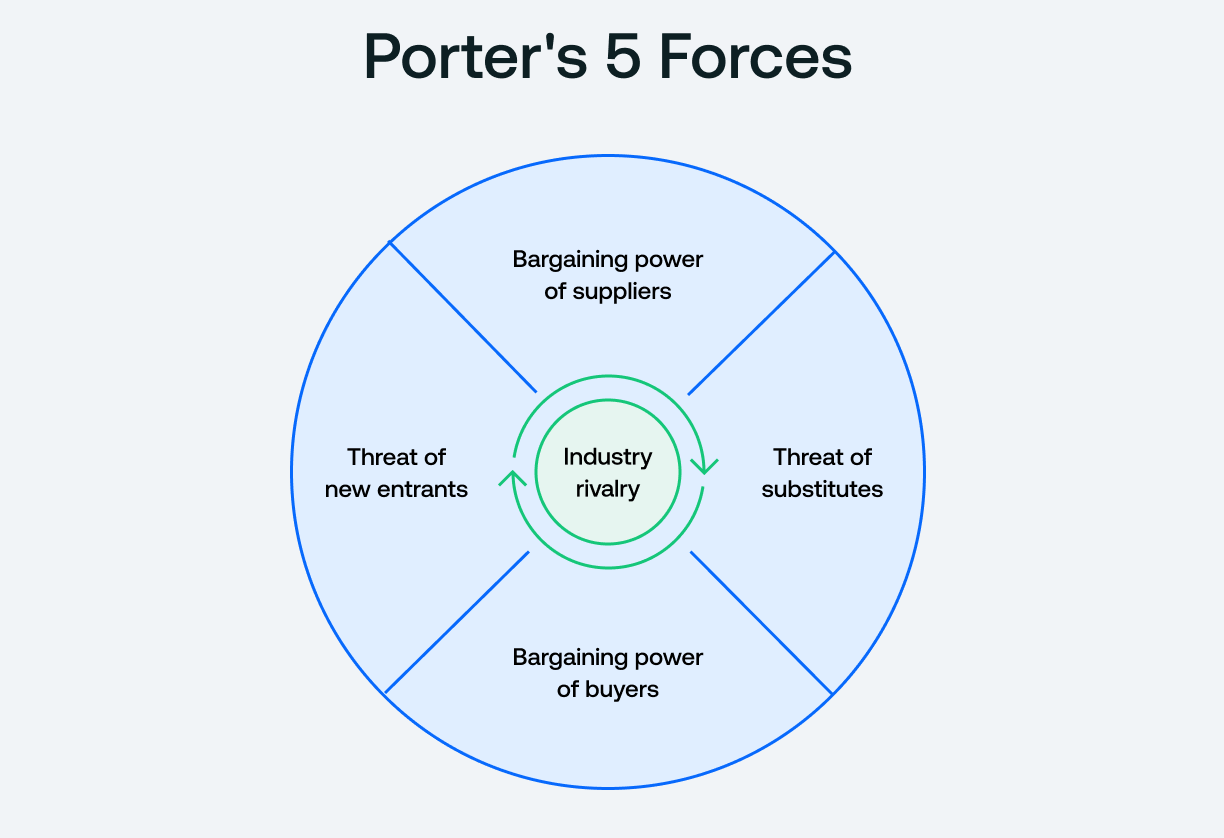

The most popular framework for business strategy is Michael Porter’s Five Forces. Porter first shared his five forces framework in a 1979 Harvard Business Review article and then covered it in his book Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. While Porter’s work dates back to the 80s, it is a valuable classic that business-minded product people should know.

Porter’s five forces are:

Rivalry from existing competitors

Threat of substitutes

Threat of new entrants

Buyer bargaining power

Supplier bargaining power

I won’t explain the five forces here; you can watch this 13-minute interview with Michael Porter where he discussed them. I always prefer to learn about frameworks directly from the creator, but if you’re pressed for time, you can watch this two-minute explainer video. In both videos, the airline industry is used as an example.

If you prefer books, I recommend Joan Magretta’s Understanding Michael Porter. She echoes many of the same points I cover in The Lean Product Playbook. Some of the key takeaways from her book are:

Strategy is about making trade-offs: It involves choosing what to do and, more importantly, what not to do. This matches my paraphrasing of Steve Jobs’ quote that I shared in my last post: “Strategy means saying no.”

Companies should focus on creating unique value for specific customer segments.

Strategy is about creating a unique position that is valuable to customers, differentiated from competitors, and sustainable.

Porter’s Five Forces is a good model for understanding the degree of competition in a given industry. For example, an industry with a high threat of substitutes, a high threat of new entrants, high buyer bargaining power, and high supplier bargaining power would be very competitive. As a result, companies in that industry would not have much market power and low profitability.

While Porter’s Five Forces framework is helpful at the industry level, it is not really designed to help at the company level, and doesn’t prescribe how a company should create its business strategy.

Profit and Growth Are Not Business Strategies

So what are examples of viable business strategies? One of the first examples that may come to mind when thinking about a company’s business strategy is something like “Our business strategy is to increase profits.” However, this is not really a strategy. This is stating a business objective, and it’s far from unique or differentiated. What company ISN’T trying to increase profits?

Another objective that is mistakenly cited as a business objective is “growth,” which is often left vague. We can consider growing revenue or growing our number of customers or growing our market share, but all of those are still business objectives, not business strategies. And again, many companies have these same objectives.

Legit Business Strategies

So what does a true business strategy look like? One clear business strategy is when a company aims to be “the lowest cost producer” in its category. The idea here is that if competing companies are charging roughly the same price for their products, the company with the lowest cost structure will enjoy higher profits. That company could potentially lower their price accordingly to increase market share and potentially drive the companies with higher cost structures out of business over time.

How does a company achieve a lower cost structure than its competitors? A common way is for the company to benefit from economies of scale. An economy of scale is when the average cost per unit decreases with an increase in the volume of production. If two companies producing the same good have the same fixed costs and the same variable per-unit costs, the company producing more units will have a lower average cost per unit.

Companies can also have a lower cost structure due to some intrinsic advantage. For example, if a particular oil company is the only one that has a refinery near the oil wells, then it would not have to spend as much money to transport the crude oil. Similar logic would apply for a paper mill that is located near the forest where trees are harvested versus other mills that are far away.

GenAI is offering potentially new ways for companies to reduce their cost structure, or put another way, increase their employees’ productivity. Advances in robotics may also help reduce costs.

Many of the examples of low-cost strategies are from the world of physical goods, which have raw material and production costs. In the world of software, things are different. With software, the marginal cost of an additional user is usually very small. Think about Gmail: How much incremental cost is there to Google for a new Gmail user? It’s very low.

Different software companies may use resources more or less efficiently, and there are outlier examples of companies who spend too much or too little based on their revenue. However, generally speaking, there aren’t usually large material differences in costs among software companies in the same space. As such, being a lower cost provider doesn’t usually create significant competitive advantage for pure play software companies. However, if you are in a very competitive space where customers have high price sensitivity, it may be relevant.

Unique Assets

Sometimes, tech companies can benefit from a unique asset. If they have unique intellectual property (IP) that lets them create more customer value and can protect their IP rights (e.g., with a patent), they may have a competitive advantage. In such cases, this topic is closely related to the company’s technology or product strategy. This type of competitive advantage is often seen in the pharmaceutical and biotech industries. It is less common in pure-play software companies.

A company’s brand can be a unique asset that results in higher perceived value from customers. Think of the large value of the Apple, Nike, and Coke brands. Building a top brand usually takes time and is often the result of a deliberate marketing strategy. Just because you have a top brand doesn’t mean all your product initiatives will succeed. New Coke and the Apple Newton are well known examples of failed products. A good brand can be helpful, but your products still need to create enough customer value to succeed (which I will cover in Product Strategy).

Network Effects

Instead of focusing on decreasing cost, you can focus on distinct ways to create more customer value than your competitors. A proven business strategy along these lines is to take advantage of network effects. A network effect occurs when adding more nodes to a network increases the network’s value. Social networking products like Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn benefit from network effects, as do communication products like Slack. The more users on each of those networks, the more valuable the network is. Tech categories where network effects are very important are often called “winner take all” markets.

Platform Plays

This brings up the topic of how to create network effects in other tech categories (besides social networking and communication). Many tech companies try to create an ecosystem or platform on which other companies can create value. For example, the iOS App Store is more valuable to app developers when more people own Apple phones, since that means there are more potential customers for the developers’ apps. Salesforce created their Salesforce AppExchange, which allowed third parties to develop applications on top of Salesforce. As more and more third-party apps were offered in AppExchange to solve customer problems, the value of the Salesforce ecosystem grew.

Successfully creating a platform with network effects increases the value of your platform to customers. It can also increase the “switching costs” for customers. While customers could switch from your platform to a different one, it would take them time, effort, and money to do so. The larger these switching costs, the less likely customers will be to switch, creating lock-in to your platform.

While creating a platform can be part of your business strategy, it would be a large part of your product strategy and potentially your technology strategy.

Business Model Differentiation

Another area where companies can create differentiation is in their business model. They may pursue an entirely new way of earning revenue. For example, before Amazon Web Services (AWS), companies had to purchase their servers and pay to run and maintain them 24/7. AWS enabled companies to pay for computing resources as they use them.

This transition from owning to renting is quite common. Until streaming services like Spotify and Amazon Music came out, people had to buy their music. Now by paying a monthly subscription fee, you can listen to any songs in their large catalogs (often called an “all you can eat” plan).

Most successful business models are well established, such as ecommerce, subscription, and advertising. Disruptive business model innovation does not happen that frequently. When it does, other companies can jump on the bandwagon and copy the innovator once the new revenue model proves successful. For example, in the cloud computing space, Google and Microsoft also offer pay-as-you-go cloud computing resources that are similar to AWS.

How defensible is your business strategy?

If your company has identified a unique business strategy, it’s important to think about how defensible it is. A strategy that can be defended over time is often referred to as a “moat,” like a moat that defends a castle from attack.

In the tech world, the most defensible business strategies tend to be network effects. Facebook has been the dominant social network since overtaking MySpace in 2008. LinkedIn has been the dominant work network since it began.

While Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android compete in the mobile phone space, each ecosystem has a large base. As of the date of this post, Android has about 72% global market share and iOS about 28%. With over 1 billion people around the world, the iOS ecosystem is definitely large enough to create and capture customer value.

As mentioned, a robust platform ecosystem like Salesforce can build a moat of network effects. In the ecommerce enablement space, there are several companies that have built ecommerce platforms, such as Shopify and WooCommerce.

If it would be relatively easy for your competitors to copy your business strategy, then it is not defensible. For example, the fact that AWS offers an on-demand cost structure for computing resources is no longer a differentiator as Google and Microsoft offer this too. These three companies compete on pricing, in which case having a lower cost structure due to operational efficiencies would be advantageous. They also compete on the features available in their cloud offerings and are constantly trying to out-innovate each other, which has more to do with product strategy than business strategy.

The reality is that only a small percentage of tech companies have a differentiated and defensible business strategy. The most common way that tech companies create meaningful differentiation is with their Product Strategy, which will be the main topic of this series.

In my next post(s), I’ll explain the other two core types of strategy—marketing strategy and technology strategy—before diving deep into Product Strategy.

If you have comments or questions about my post, I’d love to hear them. If you’ve seen a company with a strong business strategy, please share it.

I’m also collecting product strategy case studies, so if you have a good or bad example, please let me know.

Thanks again Dan. The structure and flow of the article is very clear. Jumping in to the next article in the series... :)

Good article!